Community member Fannie Smith sits in front of the Clarke Central High School ceremonial entrance on Feb. 10. Smith attended the all-White Athens High School from 1964 to 1968 before it was fully desegregated in 1970 as one of few Black students. “I experienced basically isolation and not being a part of anything,” Smith said. “Maybe there was a couple (Black students around me), two or three four of them, but it was a really small number. Most of my classes were still basically were white.” Photo by Audrey Enghauser

The desegregation of the Clarke County School District affects the educational experiences of students in the district both socially and academically to this day.

The Clarke County School District took its first steps toward an integrated educational system by selecting five Black students to attend the all-White Athens High School in 1963, 11 years after the Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education (1954) ruled racial segregation in schools unconstitutional.

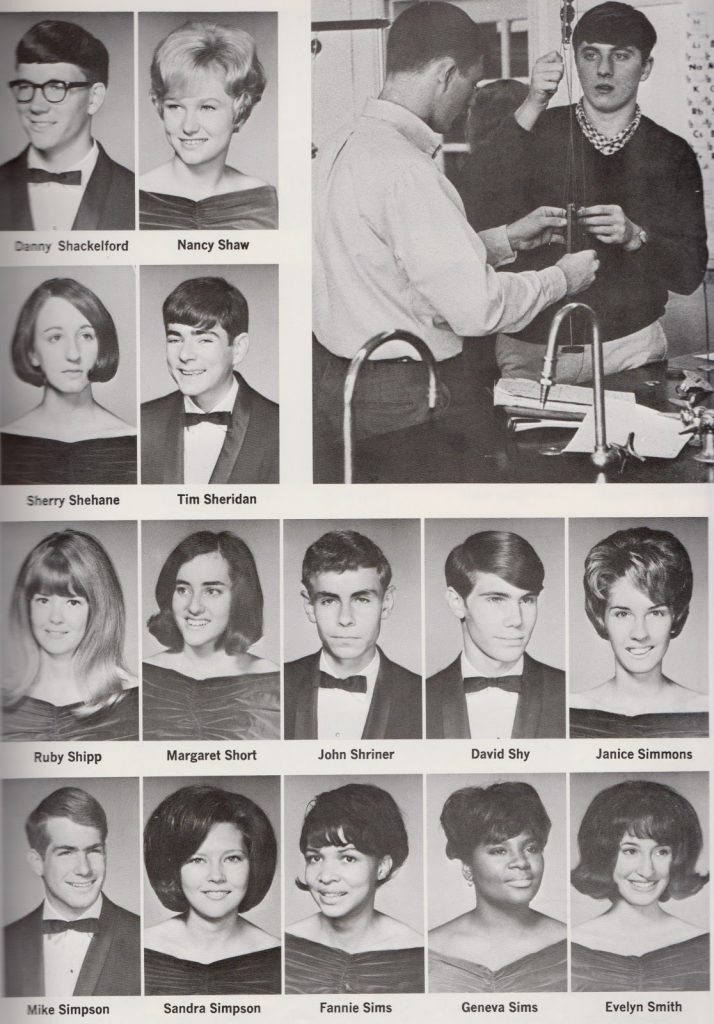

A portion of the senior class at Athens High School is pictured in the 1968 Athens High School yearbook, “The Trojan.” Community member Fannie Smith (bottom row, third from left) was one of 20 Black students to graduate from the newly integrated high school and felt isolated in the new environment. “It’s a funny feeling that you could feel fearful of white people, but (violence) really didn’t happen. You can feel that people just act like you either don’t exist, or you’re a little troubled, but they’re not gonna say anything to you,” Smith said. “(Nevertheless), I could survive by myself. I didn’t need you to be my friend to survive and to achieve in school.” Photo courtesy of the 1968 edition of The Trojan, the Athens High School yearbook

Community member Linda Davis began attending the previously all-White Clarke Junior High School, now Clarke Middle School, among the group of students who exercised their freedom of choice to desegregate the district in the late 1960s.

“My mom explained to me that we were working to help desegregate the schools and improve education for everybody in Clarke County,” Davis said. “We were (recommended), which is what probably sold us on it, because we were academically doing well. (CCSD) wanted to make sure that, in this desegregation effort, there was no doubt that Black people can learn.”

For Davis, entering an all-White school was a drastic change from her previous experiences at segregated schools and required much preparation.

“We were taught about nonviolence. We were taught to ignore the taunts. We were taught to ignore the stares, to ignore anything that anybody did to us because we were warned that it was not going to be easy, and it may not be pleasant, but we were there for a purpose,” Davis said.

The next year, Davis entered AHS, where the large number of majority-White clubs and sports diminished her participation in such activities.

“There was nothing to give us a sense of belonging. We weren’t welcome in a lot of the clubs when we desegregated these schools,” Davis said. “Leaving campus every day, we made a beeline over to (Burney-Harris High School) because we wanted to be with people that look like us, that liked us and that treated us like we were normal people.”

Community member Barbara Archibald, a current CCSD substitute teacher, attended the all-Black Athens High and Industrial School, renamed BHHS in 1964, throughout the district’s desegregation. According to Archibald, the students at her school were at an academic disadvantage.

“We lacked so many things in terms of material resources that would have helped us probably to accomplish a little bit more academically,” Archibald said. “The books, for example, were used and torn, and they were given to us after they have been used by students at AHS.”

Despite this discrepancy, Archibald feels that she received a quality education and was motivated to succeed by the school’s faculty.

“The books, for example, were used and torn, and they were given to us after they have been used by students at AHS.”

— Barbara Archibald,

Community member

“The principals would get on the intercom in the mornings and talk about (how) you were important, what you need to be doing, how education was important (and) it was the key to our success,” Archibald said. “(Segregated schools) instilled in us different values that would help us be successful in this world.”

Community member Barbara Barnett transferred from BHHS to begin attending AHS in 1965 and found it difficult to participate in the new environment.

“It wasn’t easy because we were not wanted, we were not accepted,” Barnett said. “We didn’t have the opportunity to just enjoy high school, because we were struggling with the segregation, and we were struggling with not being accepted and not wanted in the school by the students or some of the teachers.”

Barnett was one of 20 Black students to graduate AHS in 1968, alongside community member Fannie Smith.

“The only (thing) you really felt is that you were totally isolated. Once you went out of the classroom, you’re on your own, and if you went to lunch, you were on your own. It’s like you’re on an island by yourself,” Smith said.

CCSD employed freedom of choice for Black students in the late 1960s, leaving it up to families to decide which school their children should attend. For Smith, a noticeable difference in newly desegregated schools was the lack of a familiar community.

“Mr. (H.T) Edwards, who was the principal of (AHIS/BHHS), was our organist at church, so you saw him in two roles. Most of my Sunday school teachers were teachers in the school district. Some of the neighbors would teach,” Smith said. “Now you’re in the (integrated classroom), you don’t know any of these people, and so it doesn’t feel the same.”

The 1968 Athens High School yearbook (bottom) the 2019 Clarke Central High School yearbook (bottom) displays the schools’ respective senior classes. CCHS junior Camille Thomas feels that the United States has made progress on overcoming its history of segregation. “I think acceptance has been a big key. I feel like for African-Americans, (others are) being more accepted now, especially here. I feel like Clarke Central is pretty accepting of different races and things like that,” Thomas said. “In my (Advanced Placement) class, AP Environmental, everybody in there looks different. I don’t see anybody in there that looks the same as the person besides them, the person behind them. That’s progress, that everybody’s able to be an AP class like that.” Photos courtesy of the 1968 edition of the Trojan and the 2019 edition of the Gladius

Despite the growing integration of Black students into AHS, the school’s faculty failed to reflect similar demographic changes.

“I have seen our shift in who’s in charge of the classrooms go from the all-Black experience to a completely White experience (at AHS),” Davis said. “I didn’t have a single Black teacher until I got to high school, (and I had) Mrs. Ruth Hawk Payne, she was my Spanish teacher. That was the first other Black person in authority that I saw once I left the segregated school system.”

In 1970, students from AHS and BHHS began attending the new Clarke Central High School, previously AHS, and the new Cedar Shoals High School, according to their respective school zone. In Archibald’s experience as a substitute teacher at CCHS, the racial atmosphere of the school has improved over time.

“Socially, I don’t see where (Black and White) kids have a problem with each other. I don’t see that. It seems as if, from the classes that I have that I sub (for), it’s an integrated setting,” Archibald said.

“In (Advanced Placement) classes, I’m the only one that looks like me. Not that (White students) don’t include me, but sometimes I don’t (include) myself. That’s where I notice (self-segregation) most.”

— Camille Thomas,

CCHS junior

While the CCSD educational system has not been segregated in over 57 years, CCHS junior Camille Thomas notices this history impacting her daily life at CCHS in the form of self-segregation amongst her peers.

“In (Advanced Placement) classes, I’m the only one that looks like me. Not that (White students) don’t include me, but sometimes I don’t (include) myself. That’s where I notice (self-segregation) most,” Thomas said. “Teachers try (to counteract self-segregation) with the assigned seats and everything, but you always end up back with people who you’re most comfortable with.”

CCHS Associate Principal Dr. Linda Boza has noticed some students taking action on this issue in the past but has yet to see a sustainable resolution.

“We had a group of students (that) would do ‘Mix-It-Up Day’ in the lunchroom, to try to get students to sit with people they don’t normally sit with, because they recognized (self-segregation) and they wanted to change the mindset,” Boza said. “We haven’t done it in a few years now, but it was a great thing that we had going, because when students realize it and take action, that’s really what it takes.”

According to Smith, while she taught at Burney Harris Lyons Middle School from 1995 to 2011, the school’s racial demographics shifted, becoming majority-Black over time due to White flight.

“(White people) were moving to Oconee County, and they were sending their kids to private or religious school. At that time, some people would say later on that there’s a lot of stuff going on in schools, there’s violence and stuff, but that wasn’t true. Kids were wonderfully behaved,” Smith said. “Those were not the issues, but people really decided they didn’t want their kids to participate, being that kind of school. The (White) population basically never came back.”

According to Barnett, the students and faculty of CCSD have taken steps toward overcoming the district’s history of segregation in recent years.

The Athens High School sign is displayed at Clarke Central High School. The all-White Athens High School fully merged with the all-Black Burney-Harris High School in 1970 to form Clarke Central High School. “When the integration came into play, back in the ‘60s, my parents sent us to — it was Athens High School, it’s now Clarke Central,” community member Barbara Barnett said. “My parents (believed) that everybody was created equal, everybody should have equal opportunity. And they wanted their children to have that opportunity to have the best education that they could get.” Photo by Krista Shumaker

“A lot of people have learned about segregation. A lot of people have changed their mind. They have changed the way they felt (through) education (and by) getting to know people,” Barnett said. “(People started) respecting each other a little bit more, and it made a big difference. They accepted the fact that integration is here, and it’s here to stay.”

According to The Governor’s Office of Student Achievement, CCHS now has a White population of 23%, while Black students make up 46% of the student body. Thomas believes such diversity is beneficial for students.

“Being able to think outside of what you’re used to is an advantage. It teaches you a lot of life lessons, a lot of things you need to know (in) college, adult life, everything,” Thomas said. “If you’re used to the same kind of people with the same kind of mindset, you’re not going to be ready for the real world.”

Within 60 years, Barnett’s family has seen three generations of children attend AHS/CCHS, each of which have witnessed the district at various states of integration and diversity. She believes these racial changes will continue to benefit school communities in CCSD.

“I remember sitting in there at the (UGA) Coliseum (at my granddaughter’s graduation), looking at all the Black students coming through and then thinking, ‘Wow, I never thought I’d see this.’ It was more Blacks than Whites. I remember having a little satisfaction in knowing that I helped tear down those segregation walls so others, my children and other Black students, could come through easily, and not go through what we went through,” Barnett said. “It was not an easy task, but it is one that I’m glad I was a part of.”